Justice in Indian Country is a nebulous idea, mired in splintering jurisdiction, lackluster law enforcement, and severe tribal government underfunding.

Poor tribal-government relations along with government mistrust and high declination rates have only exacerbated the lack of justice administered for Native Americans and their families.

So when did this all begin?

As with most current issues, this one’s origins are rooted in the past.

How criminal jurisdiction changed in Indian Country:

- The Major Crimes Act was passed in 1885, as part of the Indian Appropriations Act. It placed violent crimes perpetrated by Native Americans in Native territory under federal jurisdiction.

- Public Law 280 was passed in 1953, as part of House Concurrent Resolution 108. It established tribal termination as the official federal policy. Public Law 280 removed jurisdiction from tribal law enforcement and transferred it to the states in California, Minnesota (except Red Lake), Nebraska, Oregon (except Warm Springs), Wisconsin and Alaska (except Metlakatla).

- The Supreme Court ruled in the 1978 Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe case that Native tribal courts did not have jurisdiction over non-Natives.

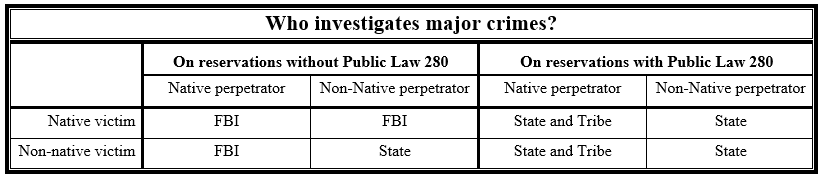

In Wisconsin, only the Menominee tribe — terminated in 1961 and reinstated in 1973 — has sovereign status, which means the FBI investigates all cases above a misdemeanor.

Tribal police function as local police departments on reservtions with Public Law 280 and prosecute through the District Attorney’s office, hence the double jurisdiction.

If a Native person is the victim or perpetrator of a crime off-reservation (in Milwaukee, for example), local police investigate; the FBI only gets involved if the person is of “tender age” and goes missing under suspicious circumstances (or committed a federal offense).

As both charts illustrate, tribal departments have very little jurisdiction over serious crimes.

And because of the Oliphant decision, tribes cannot prosecute non-Native criminals who committed offenses on their land.

Sarah Deer, tribal legal scholar and professor at the Mitchell Hamline School of Law, said the federal government’s policies — between Public Law 280 and the precedent set by Oliphant — severely undercut tribal law enforcement’s ability to do their jobs.

“Because tribes lack jurisdiction in many cases, they’re not able to protect their own people,” she said.

Underfunding and understaffing are other reasons tribes are less able to protect their people.

According to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, “tribal governments often operate with anywhere from 55 percent to 75 percent less monetary resources than non-tribal governments.”

In addition, the report pointed out how reservation law enforcement needed $337 million to make its law enforcement staffing equal to that of county government.

The report also noted that the law-enforcement-to-resident ratio is below average (3.5 per 1,000 residents) in Indian Country, which was at 1.9 per 1,000 residents during the 2010 year — in the heart of the oil boom.

That was only one way in which, as Bernadine Young Bird remarked, the tribe was not prepared for the side effects of an oil boom.

At the height of the boom, existing police issues were exacerbated by the influx of drugs onto the Bakken oil patch, where Tim Purdon, the former U.S. Attorney for the District of North Dakota, saw heroin being sold for the first time in the state.

“There was a very large spike in organized, out of state drug traffickers because of the amount of huge population growth, people with a lot of money in their pocket,” he said.

McLean County Sheriff Jerry Kerzmann, who polices an area just 90 miles east of New Town, agreed.

“We’re way busier now than we were before the oil boom,” he acknowledged.

Law enforcement agencies have begun sharing jurisdiction in their effort to address drug crimes, Kerzmann noted, despite initial hesitancy from tribal leaders.

“Tribal council leaders were hesitant because they didn’t want to give up sovereignty. (There’s) a lot of bad blood from 50-60 years ago,” he said. “Now we work together.”

Operation Winter’s End, which deployed FBI and BIA resources on the Fort Berthold Reservation to catch drug traffickers, was one particular instance of such interagency cooperation.

The effort, partially led by Purdon, resulted in 22 key arrests.

However, such successes are rare — in the year following that operation (2014), there were 5,223 drug/narcotic violations across the state.

According to North Dakota Rep. Ruth Buffalo, Native residents have little hope that cases involving missing and murdered indigenous people will reach successful conclusions.

“I think many people feel there is a lack of justice or that nothing will be done in these cases,” she explained.

Young Bird certainly felt that way when Olivia Lone Bear went missing and the family assumed a BOLO had been issued for her car — only to find it hadn’t been issued four days later.

“When the report was made, we assumed they would get a BOLO out and things would start rolling,” she explained. “So one of her brothers checked the police department in Watford to see if anything had resulted from the BOLO and they asked the officer (who) said ‘What BOLO?’”

“On the fourth day, we found out that the report hadn’t gotten in, so my brother had to go down and do the report again,” she said.

Young Bird is helping develop a protocol which will incorporate the families of a missing person into missing persons investigations.

Janet Franson was a detective in Lakeland, Florida for 21 years before she retired and spent her next 10 years working as a Doe Network volunteer, NAMUS administrator, cold case investigator and the creator of Lost and Missing in Indian Country, a website aimed at finding missing Native Americans.

According to Franson, police officers’ blasé attitude stems from a dislike of missing persons cases and a disregard for imperfect victims — sex workers, addicts and women who seem to make their own bed.

“People don’t like missing persons cases because a lot of them don’t think they’re real police-work,” she said. “I think there’s an awful lot of lazy police officers all over the place that are not investigating to their ability.”

For example, in several cases, Franson said authorities don’t look for people.

“They just (come) up with every excuse in the book. Even if she was a runaway, that doesn’t mean something bad couldn’t happen to her; that’s just not doing your job, I don’t care who you are.”

Deer said many police departments simply do not value Native lives: “The government doesn’t listen to native voices,” she said. “We’re not as significant a population. We’re not valued.”

However, Missoula Police Detective Guy Baker from Montana said his investigations have nothing to do with race.

Baker, a 29-year veteran of the force, has been looking for Jermain Charlo since the 23-year-old from the Flathead Indian Reservation went missing at a bar in January of 2019.

Baker said the aspiring artist was likely a victimized by sex traffickers.

Still, he said he has spent 2,500 man-hours, looked at half a dozen suspects, interviewed 50 people and executed several search warrants to find her.

“I have done everything for Jermain,” He said. “They trust me. They know I have good intentions. I’m doing everything.”

However, Baker appears to be an anomaly.

Families typically experience much less in the way of justice.

For example, there has yet to be a charge in the 28-year-old unsolved murder of Susan Poupart, a Lac Du Flambeau woman who was last seen getting into a car with multiple men.

The mother of two who loved to laugh and paint was found six months later as bones scattered around the Chequamegon National Forest.

Although all three men were questioned extensively and invited to testify at an open hearing, where one man invoked his Fifth Amendment, the other asked for an attorney and the third didn’t show up; at a second set of hearings when all three men were supposed to appear, the first witness asked for an attorney, prompting the officials to adjourn the hearing until December.

It is unclear whether that hearing was ever reconvened, yet charges have never been brought against the men.

Of course, even if the police referred the three men for charges, there is no evidence that the Vilas County prosecutor — or a federal one — would follow through.

Declination rates, which represent how often federal prosecutors decline to prosecute cases referred to them by police, are significantly higher in Indian Country than elsewhere.

In the fiscal year of 2013, the United States Attorney’s Office found that, over one-third (34% or 853 cases out of 2,542) of Indian country referrals for federal prosecution were declined in comparison to a national declination rate of 15% (25,629 out of 174,024 declined).

In 2017, declinations had risen to 37% (891) of the 2,390 cases referred to prosecutors in Indian Country.

It is the last link in a rusted and broken chain.

In cases where something happens to an tribal member, the case must be assigned to the proper authority, which can be difficult to ascertain without an investigation — after all, missing person cases rarely have an obvious “perpetrator.”

Then, officers must work the case diligently enough to find a body and/or a perpetrator, if there is one.

And finally, prosecutors must be willing to take police referrals.

But for Native people from Mandaree, North Dakota to Menominee, Wisconsin, justice is as fleeting as the wind.

The greatest danger with this lack of accountability, Deer said, is that it leads to Native people — and especially women — being seen as easy targets for predators.

“The system isn’t set up to protect them so that’s the reason that sex predators target native women,” She said. “The cases need to be investigated so that sends a message to predators: these women are not fair game, they are not ignored.”