In Native American spirituality, a Deer woman is a spirit entity that is associated with fertility and love. It protects women. She’s an entity that beams light.

Some tribes believed in a Deer Woman who transformed into a deer after being raped or who was brought back to life by the original Deer Woman spirit after being murdered.

For Annita Lucchesi, one of most profound moments is when she heard, a few days before a trial court hearing, about a sighting of a white deer in the city where a Native woman was a victim of murder trial.

This to her was an affirmation of the work she does, which is deeply connected to honoring those victims without a voice.

With the disparate number of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women murdered each year, the MMIW movement has become a wave of voices for the voiceless. It brings awareness about the violence against the women and girls within the indigenous population.

Lucchesi is the woman behind the research of an influential Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) report done in 2017 entitled Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG).

The report shows the starkly disparate numbers of violence against indigenous woman including trans and people from urban areas.

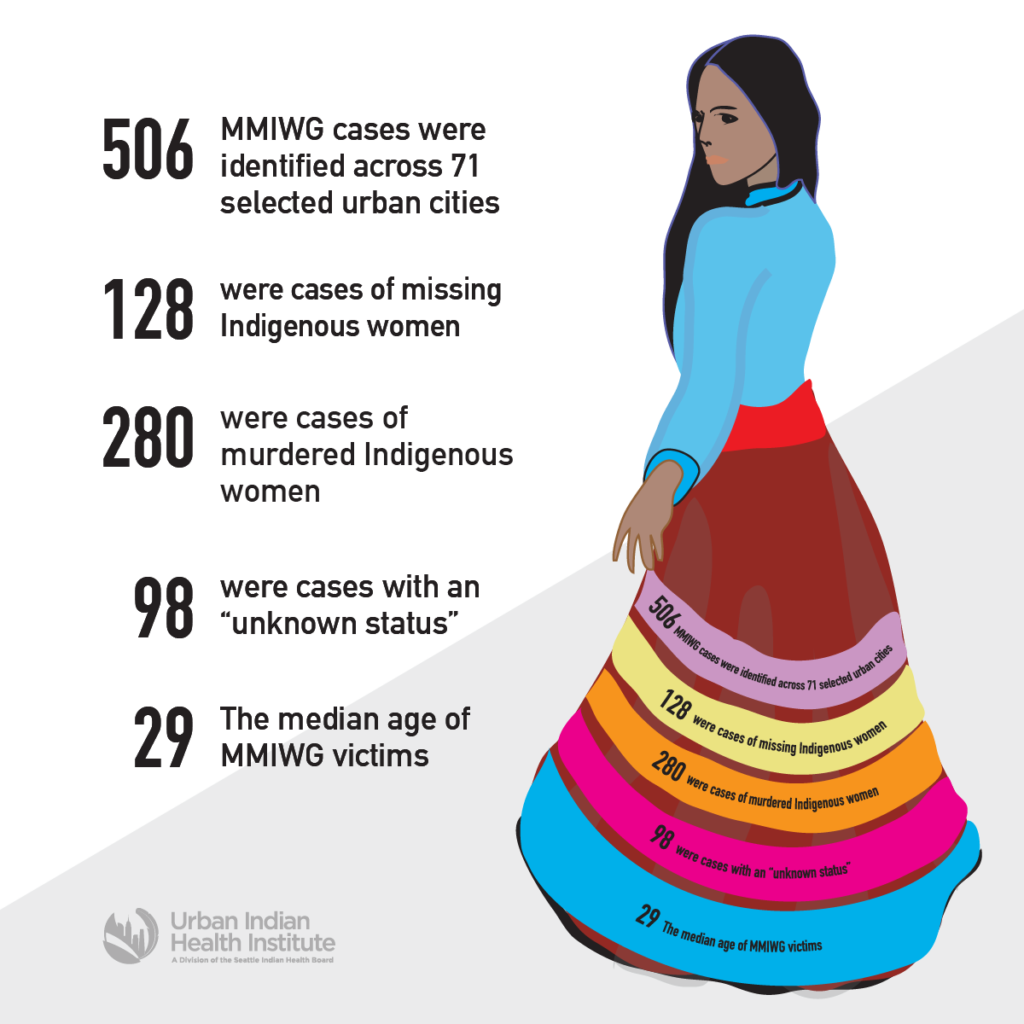

The reported collected data from 71 cities and 29 states throughout the United States.

Out of 506 cases of missing and murdered American Indian and Alaska Native women girls, 128 or 25% were missing cases, 280 or 56% were murder, while 98 or 19% were classified as unknown.

The victims ages ranged from a baby less than one to an elder who was 83-years-old.

Lucchesi started the research project because she was a survivor of sexual violence herself. “I’m a survivor of sexual violence and human trafficking… it’s a violence that almost ended my life,” she said.

The report started from a grassroots approach, says Lucchesi. Since then, the report has been used a lot and policy makers support its efforts.

Lucchesi said that some of the root causes for the start of MMIW movement are “Colonization… we had generation of Pocahontas and that’s all you see women exotic sexy this was the only image of native women.”

The report says that some of the problems of accessing data about missing and murdered indigenous women involved lack of records and racial misclassification.

The report surveyed 71 cities’ police departments and one state agency; 40 agencies provided some level of data, 14 agencies did not provide data, 18 agencies still have pending requests under (FOIA) Freedom of Information Act laws.

The report analyzed the media coverage of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls. The authors examined 934 articles, which only covered 129 cases out of 506 represented in the study.

The results were that one-fifth of the total local cases were covered more than once, which is equivalent to 14%. In less than 1/10, the cases were covered more than three times, or 7%.

Another analysis from the media analysis dealt with violent language.

UIHI defines violent language as language that engages in racism or misogyny or racial stereotyping, including references to alcohol, drugs, sex work, gang violence, victim criminal history, victim-blaming, making excuses for the perpetrator, Misgendering transgender victims, racial clarification, false information on cases not named in the victim, and publishing images / video of the victim’s death.

Lucchesi connects the complexities of violence against Native women through this analogy.

“Look at it like soup, but ultimately you want to have a good soup. We just want a good soup. If the root cause of these issues is colonization you can’t expect to add more colonization, and to have it move differently…Tribes should be notified when people go missing. This could be impactful.”

She suggests “rethinking and making the small changes that honor that type of coverage.”

The MMWIG report states that law enforcement lacks access to data regarding this issue, which can impede the ability for communities, tribal nations and policymakers to make the best decisions to address these issues. As a result, grassroots approaches by community members must be the sources used to address issues with Indigenous women.

The study also says that racial and gender disparities in police forces contribute to the treatment on how MMIWG cases are handled.

Lucchesi considers her work as a spiritual work. “A data-based is a process of prayer for me.” That’s a process she feels her ancestors assist her with.

“I learned self-care through the data a process as prayers. I don’t add to the database every day…The process of the database is a deep sense of urgency,” said Lucchesi, who added the process helps “all these spirits,” meaning that as a result researching the data is “not all sad but brings some closure.”

She feels that her work honors those spirts of the women and girls to move on and go home.

Lucchesi currently works as the Executive director of the research institute Sovereign Bodies Institute (SBI).

The Institute gathers data and knowledge to put action in place to dismantle and create change on gender and sexual violence against Indigenous people.

SBI is affiliated with the seventh-generation fund, a non-profit for indigenous leadership for the past 40 years.

Her plans for the future is to expand her data collecting to the Indigenous women populations in Latin America.