North Dakota. High noon. Plains browned by a long winter lie under the backdrop of a blue sky dotted with picturesque clouds.

Suddenly, oil wells and fracking stations scar the tranquil scenery as one crosses the boundary onto the Fort Berthold Reservation.

Semis routinely thunder by, their wheels spraying swirls of dust, blanketing the landscape in a russet haze, as if to remind its residents, things will never be as they were before the oil boom.

At midnight, flares will light the sky like campfires for the stars. The horizon is surrounded by a flickering orange glow in all directions: an endless sunset.

On a normal night, you can no longer see the stars, as flares hiss and belch natural gas fireballs into the sky.

A kitschy, wooden cowboy stands with his arms posed in an awkward embrace near a stoplight. The Bureau of Indian Affairs building stands imposingly across a small plaza with a bead shop, jewelry store and plastic oil well.

Farther down the street sits a billboard advertising apartments for $1,500 monthly rent, as an errant tumbleweed somersaults across the road – signs of how much things have changed.

“It’s a shock for me every time I go off; to me, it doesn’t even look like home anymore,” Bernadine Young Bird said, her face wistful and sad. Young Bird is a faculty member at Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College and member of the Maxoadi Hidatsa clan, where her people used to roam the lowlands before the government flooded them to create Lake Sakakawea.

Now, that once pristine Indian country is home to hundreds of mechanical arms violently pulling oil to the surface to be sent down the “Black Snake” of the Dakota Access Pipeline, which starts here.

It is also home to one of the most high-profile once missing indigenous people in a country with too many of them: Olivia Lone Bear, Young Bird’s niece.

The oil powers towns across America, funds schools and health centers on the reservation, provides checks for once-impoverished people and employs thousands of oil workers, self-described rock n’ rollers and drifters who pour into the community from all over, bunking in makeshift “man camps” and overrunning hotels.

But not everyone in the Bakken Region’s shale haven is “oil-rich.” In fact, the reservation is stratified by those who leased their land to the oil companies, those who refused to do so and everyone in between.

Prices rose to levels only those profiting from the oil could afford and crime and pollution rose to levels many of the Native residents had never seen before.

Nearby business chains were forced to import workers from Africa, as minimum-wage jobs sat empty in the oil economy. Frac sand was carted to the Bakken from Wisconsin.

In 2018, North Dakota produced 11.5% of the nation’s crude oil, second only to Texas.

Before the oil, government extermination and termination policies, poverty, drugs and disaffection ravished reservations, leading to domestic violence, higher rates of suicide and, yes, murdered and missing indigenous people.

After the oil, these existing ills worsened.

“I feel like we’re going extinct,” Francia White Body, a tribal Head Start worker, said as she walked out of the Better B Cafe, the local watering hole in New Town, the main outpost on this western North Dakota reservation that is home to Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara people (former rivals now called the MHA Nation or Three Affiliated Tribes).

But for Young Bird, the oil and missing and murdered people are but the latest of many acts of violence visited upon the Native people, which is how many here describe themselves.

“When you think about our history, it’s a story of survival,” she said. “My people are very resilient.”

Twenty-eight-year-old James Phelan, a Hidatsa cultural leader, has kept that fighting spirit alive with his passion for tradition.

Students encountered Phelan loading wood for a traditional sweat lodge ceremony into his truck outside a one-stop-shop in Mandaree, a reservation town so small that it lacks a library and grocery store.

From the outside looking in, it may seem as though the residents do not have much.

However, as Phelan later explained before the purity of a sacred fire, the strength of North Dakota’s Native people lies in their fealty to profound intangibles:

Culture. Heritage. Community. Spirituality. And a traditional reverence for protecting the Earth.

Phelan, who belongs to a tribe once whittled down to 100 people from smallpox, said the elders are the tribe’s heartbeat.

“It’s a beautiful thing to be Native American,” he said.

But to be Native American is also to be imperiled.

According to a 2008 National Criminal Justice Reference Service report submitted to the Department of Justice, “Some counties have rates of murder against American Indian and Alaska Native women that are over ten times the national average.”

And in a 2018 report by the National Congress of American Indians, researchers found that more than half of Native women have experienced sexual violence and/or intimate partner violence.

“That’s why they call it the Wild West,” said Josephine Espino, the business administrator of Mandaree Public School.

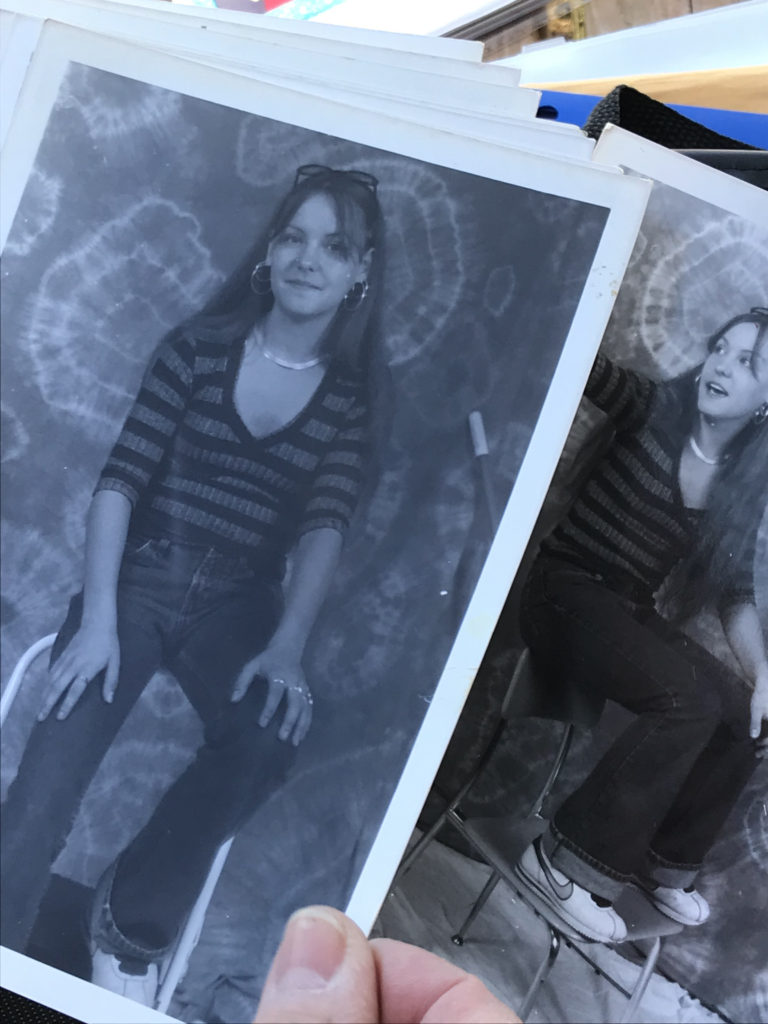

Olivia Lone Bear made that wild country her home, caring for her father and four children and befriending those working in the oil fields.

Beautiful and spirited, she had pride in her heritage and wore it in the form of a tattoo on her arm which read, “Lone Bear.”

Last seen leaving Sportsmen Bar in an oil worker’s truck, she vanished, leaving behind questions, frantic relatives and another name to add to the growing list of missing and murdered indigenous women.

To better understand the topic of missing and murdered indigenous people nationwide, seven diverse journalism students from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee spent three months exploring the issue. They contacted every tribe in Wisconsin for statistics and spoke to families in four states.

The students also traveled to New Town and Mandaree, North Dakota, small communities on the Fort Berthold Reservation, where they found a people struggling to survive the aftermath of an oil boom.

Although DAPL sparked protests that drew national media and celebrity attention, not far from where the pipeline starts, oil quietly permeates the landscape. Media coverage of the DAPL narrative focused on water, while the realities of what it carried — oil — were largely left out.

Drugs, prostitution, accidents, disappearances and occasionally, murders, have turned the quiet reservation into a place Young Bird drives through hunkered down, hoping to make it home without being crushed by a semi.

“It used to be a beautiful drive,” she said. “Today, you’re just white-knuckled, driving and watching for the trucks.”

Seventeen hundred wells blotted federal and Indian reservation lands in 2017, according to the Bureau of Land Management, pushed there after President Obama cracked down on fracking in 2015 — rules the Trump Administration rescinded in 2017.

“We’re like rock ‘n’ rollers. We work all day, drink beer all night, and then move on to the next place,” said an oil worker from Arkansas as he smoked a cigarette outside New Town’s Teddy’s Residential Suites, a hotel crawling with men from all over the country. Every morning like clockwork, uniformed workers climb onto a company shuttle. He, like others, refused to give his name out of fear his company would not approve.

During 2017, there were 10,642 entries for missing Native Americans according to the FBI’s National Crime Information Center. Last year, 9,914 such entries of missing Native Americans were made.

But the data is less clear on reservation land, where tribal data, if collected, is often not shared with the public.

Two women determined to see Native people counted uncovered over 500 cases of missing and murdered women and girls in various cities across the country as part of their report.

Annita Lucchesi, a doctoral student, and Urban Indian Health Institute Director Abigail Echo-Hawk compiled a 24-page report in 2018, where they analyzed data collection efforts, police efficacy, media coverage and victimization trends.

They also found 506 instances of missing and murdered native women and girls in those urban areas, 95% of whom never received national media coverage.

They found that most Native people (70%) live off-reservation, making it more difficult to track crimes due to race misidentification.

To be sure, although Fort Berthold locals say oil has driven up crime (drugs, sex trafficking), the issue of missing and murdered indigenous people is a causal braid both here and elsewhere, not always linked to oil. There’s Native on Native violence, white on Native violence, domestic violence, sexual violence, a meth epidemic and those who simply vanished into thin air. The common thread: More than two centuries of oppression.

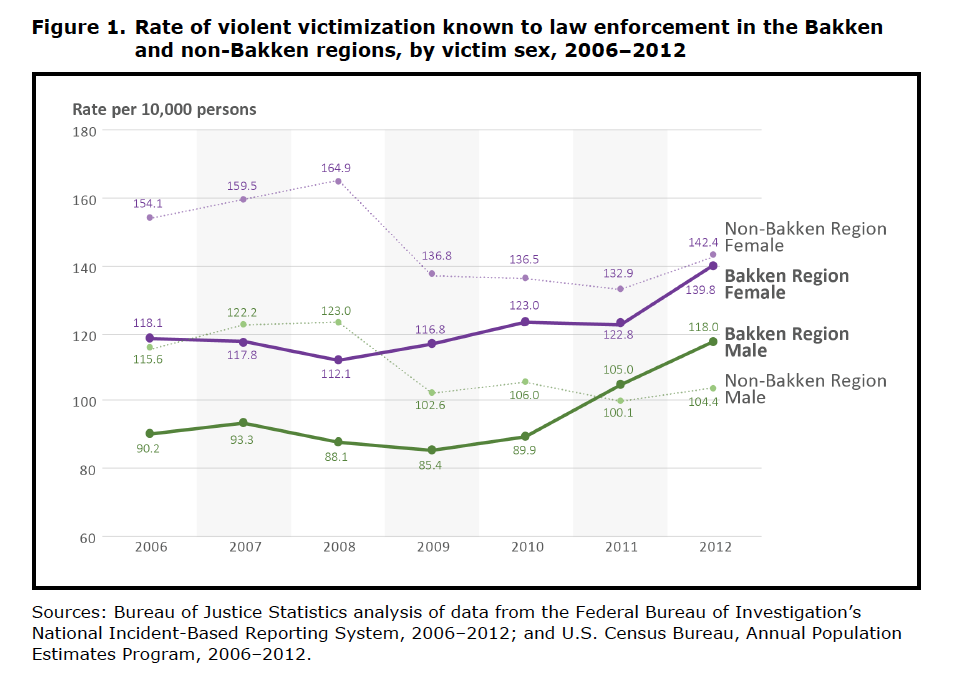

A report funded by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics found that, from 2006 to 2012, the rate of “violent victimization known to law enforcement in the Bakken oil-producing region of Montana and North Dakota increased, particularly the rate of aggravated assault, which increased 70%.”

“There was no similar increase in rates of violent crime in the counties surrounding the Bakken oil region,” the study concluded. “Rates of male and female violent victimization in the Bakken region increased during this period, with the increase being higher for males (up 31%) than females (up 18%).”

Rick Ruddell, author of “Oil, Gas, and Crime: The Dark Side of the Boomtown,” also studied crime spikes near oil fields.

“Everybody living in a boomtown suffers from a reduced quality of life due to antisocial behavior and crime, the disruption of long-standing routines and relationships, and the environmental impacts of development,” he wrote.

He also found that women were afraid to go out at night, wait for public transportation and even walk by themselves during the day.

Lucchesi said that fear is borne from centuries of being stereotyped as the “sexy savage.”

“On colonial occupations, we had generations of Pocahontas and all you see ia women who are sexy and exotic,” Lucchesi said. “This was the only image of native women.”

An analysis of the Marcellus shale region in the east coast states of New York and Pennsylvania found that violent crime increased 35% in counties with high amounts of fracking between 2004-2012.

And in North Dakota, Ruddell noted how the number of registered sex offenders increased in the Bakken region between 2000-2014 compared to counties with less oil activity.

Ruddell’s research also found that men are more likely to be victims of violent crime, despite receiving less media attention.

This disparity has prompted some community leaders to create a more inclusive #MMIR — missing and murdered indigenous relatives.

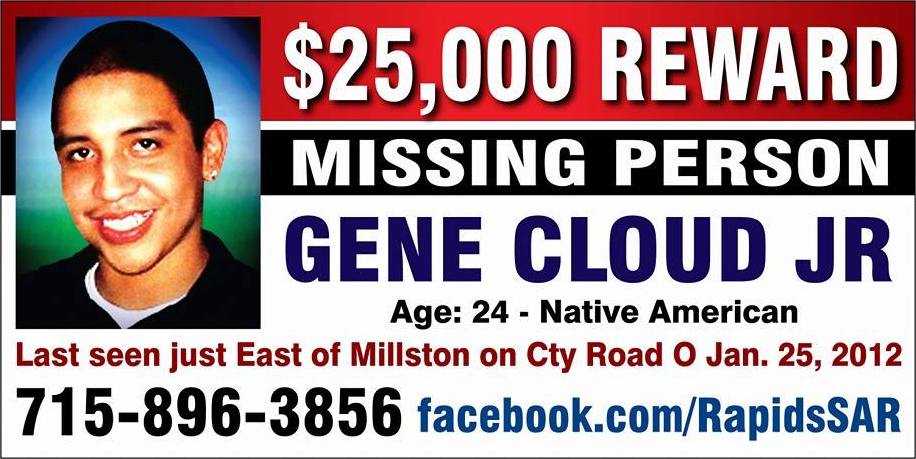

Relatives like Gene Cloud, Timothy Thompson and Daniel Skenandore from Wisconsin who have not been seen in years since their disappearances.

The disparities in enforcement and coverage are rooted in termination policies and crime legislation that stripped tribal law enforcement of their ability to prosecute non-Natives who commit crimes on reservation land.

Consequently, jurisdiction, despite efforts to cross-deputize and share information, has become a nightmare.

McLean County Sheriff Jerry Kerzmann said agencies must work together to improve how they handle sudden rises in crime.

“By not having a relationship, we are empowering drug dealers, addicts, and the people being affected,” he said. “It’s a time now when we need everyone with a badge and gun working together to resolve these problems.”

Most jurisdiction rules are based not only on where a crime occurs, but the tribal status of the victim and more importantly, the tribal status of the suspected perpetrator.

In missing persons cases, responding officers must determine whether an adult’s disappearance is suspicious enough to warrant police intervention at all, before attempting to bring in other agencies to work the case.

As a result, women like Olivia Lone Bear are lost in the confusion.

Lone Bear’s brother had to file two police reports after the first was never recorded and Young Bird said there was no BOLO issued for her truck until days after her disappearance.

Lone Bear’s family organized, searched and publicized Olivia’s case in a campaign few families of missing indigenous people have the resources to mount.

They conducted multiple land searches and begged city officials to check the waterways.

Then one month turned into nine, and the family was left searching for answers until two fishermen caught a strange ping beneath the blue majesty of Lake Sakakawea and found Lone Bear in the truck submerged below the surface.

The discovery of her watery grave has left the family with more questions than answers as they desperately chase a feeling that goes beyond the simplistic word, “closure.”

Editor’s note: Each chapter included some reporting from other members of the student journalism team.