The MHA people have a long, storied history that goes back centuries before any Europeans even settled on this continent. They have schools, families and communities much like what you might find in other American small towns. And many of them are actively working to preserve and celebrate the culture that keeps them who they are.

“We were very self-reliant,” said Bernadine Young Bird, a faculty member at the Native American Studies and Cultural Center and instructor on traditional gardening. “We relied on the skills and knowledge that our people had.”

Young Bird maintains the contemporary gardening methods of her people. She sees this as both a way to reignite her people’s “love and need for gardening” and as a way to bring some food sovereignty to a town filled these days with pizzas and canned goods. Young Bird said the reservation has high rates of diabetes thanks to the “American diet.”

Her people traditionally grew beans, squash and corn. Young Bird called these “the three sisters.” She also likes to grow sunflowers. She maintains her garden in the traditional Hidatsa way with traditional hidatsa tools. Her 85-year-old mother, a fluent speaker in Hidatsa, is helping her record the names and techniques of their people for future generations to appreciate. And she isn’t nearly the only one working to preserve and celebrate the MHA ways.

James Phelan is the cultural advisor for his segment of the reservation. He hosts a sweat lodge several nights a week, or whenever somebody asks him to.

Sweat lodges are Native American ceremonies meant to bring some form of peace to anyone struggling. At least 40 rocks are placed under a roaring fire for hours and hours until they turn red hot. Then, everyone enters the lodge and gathers in a circle around a pit dug in the center. The red-hot stones are brought in one by one until exactly 14 sit glowing in the middle. Someone is chosen to say a prayer for those in the lodge and spread chips of cedar over the rocks. The cedar cracks and sparkles on the rocks and releases a pleasing aroma throughout the tent. Several in the tent then sing traditional Hidatsa songs and splash water over the stones until the tent is thick with steam.

James says the ceremonies take a lot out of him. But he can’t control when someone needs help, and he always wants to be there when needed. He says it also reinforces his spirit. The rocks can’t be used again because they contain celebrants’ toxins. Here, the fire is pure.

He also likes to sing outside the lodge with his friends and in competitions. Phelan and his friends sing Hidatsa songs together for community events and powwows. He said he even sang for the Netflix series “Longmire” in an effort to bring traditional Native American music to mainstream television.

“The beautiful part is our culture,” Phelan said.

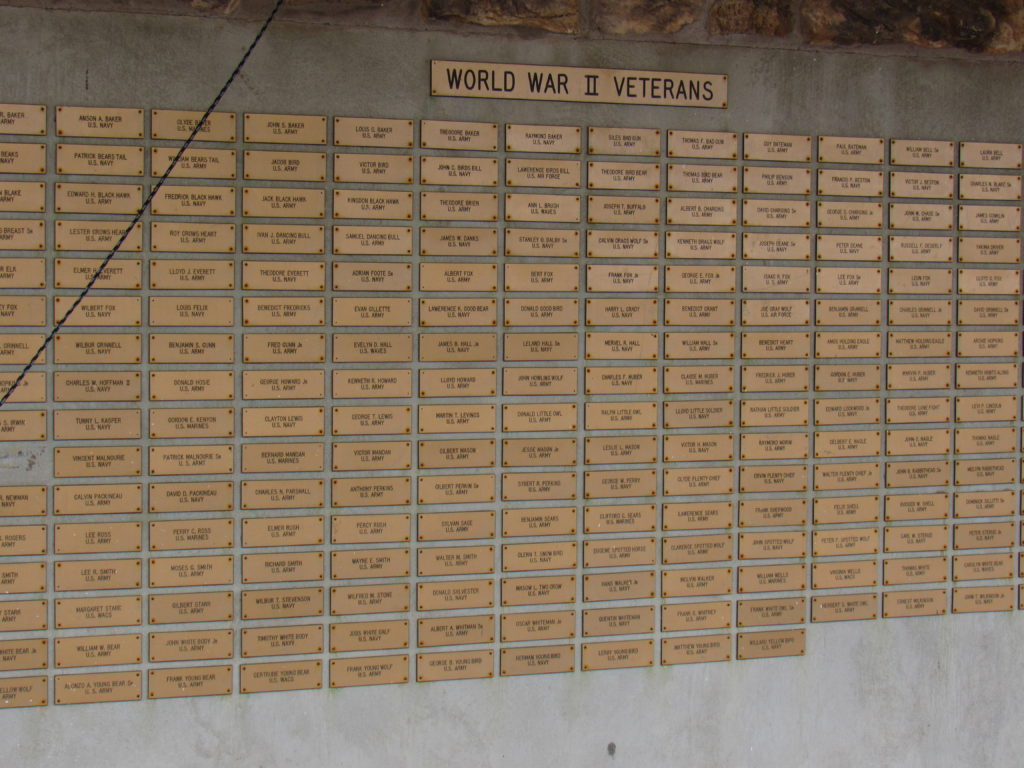

James said a big part of their culture is honoring veterans. You can see this when driving through town. Right next to the statue of Chief Four Bears, the MHA’s most honored leader, is a memorial to all MHA tribal members who gave their lives fighting in American wars.

The demographics of Fort Berthold are changing. With the oil came many non-native people from all over the United States. James Moren, a supervisor for the traditional Long Earth Lodges, said he doesn’t mind the influx of new faces “as long as we can get together and have a good time.”

“If you’re going to stay and work, then you’re going to make this place home,” Moren said.

Powwows and ceremonies are held on the regular in Fort Berthold. People from different nations all over the North American continent flock to these powwows, adorned in the ceremonial garb of their nations. Some come to dance. Some come to sing. Many come to socialize and enjoy the show.

“The more you come to the powwow, the more people you know,” said Mary Topsky, a dancer during a memorial powwow for the late singer Kenny Merrick Jr. “I feel really comfortable when I come here.”

Topsky has attended powwows since she was a little girl. She said she considers powwows to be a sort of family gathering.

Not only are there those hard at work to protect and express their Native American culture, but there are also some out there fighting to protect the people. Anita Lucchesi is one such person.

She is the creator and executive director of of the Sovereign Bodies Institute, an organization dedicated to ending sexual violence against Native Americans by empowering communities through data collection.

“When I first started, I knew that it’s going to be my life’s work,” Lucchesi said.

She said she considers it an honor to help bring women “a home” with the community her organization provides after they’ve gone through a traumatic incident.

There are efforts all throughout Fort Berthold to preserve and celebrate where they’ve come from and what they are. They work hard to keep the community strong and will go out of their way to care for another in need.

“Hopefully, you’ll see more of us than just the oil,” Phelan said.