A few short years ago, the Fort Berthold Reservation consisted of only a handful of sleepy towns. The population hovered beneath 10,000 people spread out among nearly 1 million acres. Few locked their doors and many of the country roads remained unpaved. Some families had 16 people living within the confines of a two-bedroom home. They survived off of commodity cheese and other processed foods. The oil boom changed it all.

The United States Geological Survey estimates there’s somewhere between 4.4 and 11.2 billion barrels of still-undiscovered oil waiting to be drilled within the Bakken, a 200,000 square mile ancient rock formation between Montana and North Dakota. Companies extracted around 450 million barrels just between 2008 and 2013.

“This doesn’t even look like home anymore,” said Bernadine Young Bird, a New Town local and faculty member at the Native American Studies and Cultural Center.

The oil has always been there. And those interested in the black gold always knew it. The problem was that the rock formation used to be too difficult and too costly for any self-respecting capitalist to justify drilling. So what changed in 2008? In one word: fracking.

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a process in which a pressurized fluid, composed of a cocktail of water, sand and multiple chemicals, is pumped deep into the earth to crack the ancient stone and release oil trapped within. Once released, the oil can then be gathered up and shipped down the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) to Illinois for processing.

Although fracking has existed since the ’40s, it only became affordable and mainstream within the 21st century. Essentially overnight, hundreds of thousands of oil workers descended upon Fort Berthold and began drilling. From 2009 to 2014 alone, an extra 100,000 people descended into the area. “North Dakota led the nation in population growth over the past five years, at 12%, and men have accounted for two-thirds of it,” Pew Research wrote in 2014. Men formed a larger proportion of the North Dakota population than any other state but Alaska.

Landowners leased their property to the oil companies for tens of thousands of dollars a month. For the first time in a long time, real money flowed through the fingers of many Fort Berthold residents. But the newfound wealth didn’t spread evenly.

Those tribal members fortunate enough to find oil underneath their land saw more cash than was at one point ever dreamed possible. They bought nice cars and expensive clothes. You might even see a pristine Hummer pull up to the post office in a town too poor to have a grocery store.

Some people left and bought homes in places warmer and sunnier than North Dakota. For the rest, not much changed. If anything, their situation might’ve gotten worse.

In the beginning, the police force of Fort Berthold had only a handful of squad cars. They were a small town department used to dealing with small town problems. The oil workers, mostly men brought from all over the country and from all walks of life, found themselves making a starting salary of $100,000 a year with nowhere to go and nothing to spend it on. Some used the money to support families back home. Others used it to party like there’s no tomorrow.

Oil workers smoke cigarettes outside New Town’s Teddy’s Residential Suites, a hotel crawling with men from all over the country. Every morning like clockwork, uniformed workers climb onto a company shuttle.

Violent crime rates skyrocketed within the Bakken. Aggravated assaults rose by 70 percent between 2006 and 2012. Residents of these sleepy towns had to think twice now about locking their doors.

From 2006 to 2012, a Federal Bureau of Justice Statistics-funded study found, “the rate of violent victimization known to law enforcement in the Bakken oil-producing region of Montana and North Dakota increased for males and females.”

“The violent victimization rate for males increased by 31%, from 90.2 per 10,000 males in 2006 to 118.0 per 10,000 males in 2012, whereas the comparable rate for females increased by 18%, from 118.1 per 10,000 females in 2006 to 139.8 per 10,000 females in 2012.”

The researchers noted that there were not similar crime spikes in non-Bakken counties in the same region: “Violent victimizations include the offenses of murder, rape and sexual assault, other unlawful sexual contact, robbery, aggravated and simple assault, kidnapping, and intimidation. During this same period, the rate of violent victimization in the non-Bakken counties of Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota, decreased for males (−10%) and females (−8%). “

In 2015, authorities responded by creating the “Bakken Organized Crime Strike Force.” In a press release, the Department of Justice noted, “The Bakken is a vast swatch of oil-rich land spanning approximately 200,000 square miles from North Dakota to eastern Montana and north to Canada. It has resulted in dramatic influxes in the population as well as serious crimes, including the importation of pure methamphetamine from Mexico and multi-million dollar fraud and environmental crimes.”

Jeanine Spotted Horse, a mom from Mandaree and worker at the local high school, remembers hearing more and more stories of strange men trying to lure young girls to their car.

“We couldn’t even have our kids play outside,” Spotted Horse said.

The villages of Fort Berthold weren’t prepared for the population explosion that came with the oil boom. A lonely motel and a handful of apartments couldn’t hold back the tidal wave of a housing crisis that hit Fort Berthold during the boom.

Charlie Moren, a Hidatsa language high school teacher, said he saw office space, bowling alleys and movie theaters all get converted to housing units. He wore wide glasses and a cowboy hat and took drags of his cigarette real slow. He bragged how a local food truck named a signature cheeseburger after him.

He said he saw tenants evicted from their apartments, only to see the place put back on the market for triple the rent. Moren said he saw some two-bedroom places listed for $3,000 a month.

“We had rent prices higher than in New York City,” Moren said. He said he receives some oil money from the fracking companies but didn’t say how much. Other tribal members insist they know people getting oil royalty checks exceeding several hundred thousand dollars a month.

Many companies placed their workers in temporary constructed work camps. These “man camps” were everywhere during the boom. Some functioned like a military base, with mess halls and libraries and community centers. Others operated like the setting of an old spaghetti western film, dangerous and full of anarchy.

These days, the man camps have mostly disappeared. But there are still some campers and mobile homes parked near oil sites. One such site sits nestled between a drill site and a dirt parking lot for semi trucks. A nearby sign at an empty and overgrown jungle gym reads “children at play,” the pumps and burning flares of the worksite just a short stroll away. A red pickup has a “Trump 2016” bumpersticker.

The bulk of the workforce now stays in newly-constructed hotels. Teddy’s stays near full capacity on a regular basis. The building is multiple stories high with a bar and restaurant in the lobby. The place still smells like timber and fresh paint.

Oil workers come and go through the lobby in their bright green reflector jumpsuits with the Calfrac Well Services company logo labeled on the front. They mostly keep to themselves these days.

Most refused to give their names or speak about their jobs. One such worker said his supervisor explicitly warned them not to talk to the reporters staying at Teddy’s under any circumstances. Three oil workers did agree to talk but only without their names.

“You don’t have to go to college, you don’t have to have a high school diploma, and you can make over $100,000 a year,” commented a 19-year-old from Washington State.

“I wouldn’t even take a job under 100k,” joked the eldest as they all laughed together. He claimed the companies don’t all thoroughly check backgrounds of workers, calling some of them “ruffians.”

And that isn’t even to say what happened to the landscape. Before the oil can be pumped to the surface for transport down DAPL, first comes the natural gas. There are two ways to deal with natural gas; you can capture it and process it for energy use, or you can simply burn it off into the air and make room for the oil. The companies at Fort Berthold chose the former. The tribal government helped open the door to them.

The protests around the Dakota Access Pipeline drew national attention and celebrities, but a few miles away, oil dominates the reservation landscape with far less hue and cry or media scrutiny. From the top of a hill outside New Town, you can see metal spires jutting from the earth and spewing fireballs of differing sizes into the atmosphere. At night these flares light up the sky. On many nights you don’t see the stars due to light pollution.

Any night map of the reservation is illuminated with thousands of specs of light. The place looks more like a bustling mid-level American city than a sparsely-populated section of North Dakota littered with oil rigs.

Many locals now fear what the oil is doing to the land around them. Some are scared to eat fish from the rivers or hunt local game. They say the wildlife is gone. What does the after burn of the flares leave floating around in the air for everyone to breath?

“The oil has corrupted the water, the air and the people,” said Lesa Fox, a gas station clerk in Newtown who recently moved back to the reservation after living elsewhere for the last 22 years. She said she plans on leaving again soon.

But what the people consistently said they hated the most from the boom was the semi trucks. Fleets of semis carrying oil, water or supplies came barreling through towns and highways on a regular basis. People died in head-on collisions with trucks taking a sharp turn and going too fast. The road from New Town to Mandaree features multiple crosses near its edge. Each one marking the site where someone met their end.

As far back as 2001, the MHA Nation declared in a resolution that “one of the leading causes of death and injury on the Fort Berthold Reservation each year is traffic accidents.” Some of the traffic was attributed to the casino and economic development.

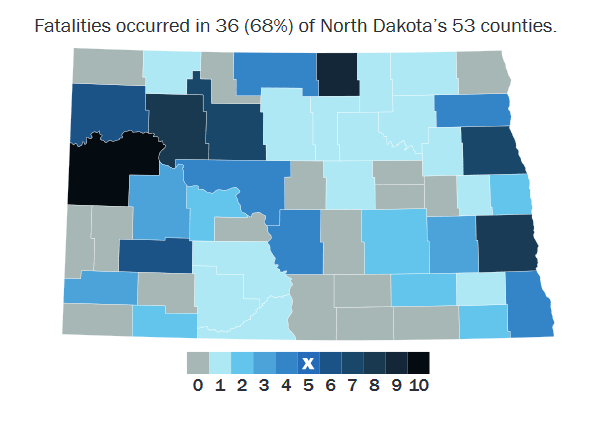

A 2017 state report says that motor-vehicle crashes are “the leading cause of injury-related death in North Dakota,” and almost half were alcohol-related. However, in 2014, the number of statewide crashes began to recede. From 2008-2014, the state was above the national fatality rate in all but one year.

A state chart shows that fatalities are greater in number in the western area of the state dominated by the Bakken shale. As recently as March 2019, The Bismark Tribune reported that a head-on semi crash led to a fatality on Highway 23 bypass in New Town. Two Arizona people in a pickup, David Wilcox and Taylor Denny, were killed. The semi driver, who was from Montana, was accused of negligent homicide.

The Upper Great Plains Transportation Institute found that “the majority of truck-involved injury crashes occur in the oil region” in North Dakota, according to the Tribune.

“I always used to like driving to Mandaree,” Young Bird said, fumbling her hands over one another. “Now, it’s terrifying.”

The natural beauty of the land is now lost on many a traveler. One must drive white-knuckled down every stretch of road, constantly vigilant for some truck turning a corner and swerving too far or driving too fast.

The roads weren’t even paved in those days. The constant barrage of trucks on the highways kicked up a storm of dust that settled over everything in the area. It was as if the days of the dust bowl had returned.

Spotted Horse, the Mandaree school worker, said she believed the dust made her and her horses sick. Her kids would come home covered from head-to-toe in a layer of dust. The swimming pool her family put up just before the boom got reduced to an unswimmable brown sludge.

James Phelan, the cultural advisor for his segment of the reservation, hated the semis. He wore a New York Yankees ballcap and drove a large black Chevy pickup truck. While normally quick to make a joke, talk of the semis brought a scowl to his face.

He said he made his own speed bumps and placed them on the roads in town to force trucks to drive slower. And it worked. The companies eventually gave in to the people’s frustrations and agreed to pave the roads. The Mandaree government even set up new laws dictating semi traffic to drive around the town, instead of through it.

The MHA people remain conflicted over what the legacy of the oil should mean to them. On the one hand, the boom brought drugs, crime and pollution to friendly communities where, at one time, everybody knew everybody else. It caused internal conflicts with traditional philosophies about protecting the earth. On the other hand, the oil paved their roads and built new schools and community areas. It lifted people out of poverty with large royalty checks.

Mandaree’s high school doesn’t have its own football field. Every game has to be an away game. Thanks to the oil, it’s scheduled for a multi-million dollar renovation. Families with generations trapped in poverty suddenly found themselves flooded with cash.

Spotted Horse said she doesn’t think the tradeoff was worth it. She has a son who works in the oil industry. Others aren’t so sure.

“People own their own businesses now and can take care of their families,” said James Moren, Charlie’s son and the Long Earth Lodge supervisor.