When the face of a missing person flashes across a television screen, it sends a message to those watching:

This person is valuable, someone misses them.

But rarely, according to Zach Sommers’ 2016 report, is that message sent for Native Americans.

After studying five news sources (the Atlanta Journal-Constitution without AP contributions, Atlanta Journal-Constitution with AP contributions, the Chicago Tribune, CNN and the Minneapolis Star Tribune), he found that “Missing White Woman Syndrome” is not just a catchy phrase, but a media reality.

Four of the five sources he analyzed overrepresented women and white missing people compared to missing men and people of color, respectively.

And Sommers found even greater disparities when he looked at the intensity of coverage, where half of the coverage covered missing white women as their subjects.

“… Whites, women, and likely white women in particular benefit from a higher intensity of coverage than other missing persons,” he concluded.

In contrast, missing Native American men seem the least likely to benefit from this type of coverage.

Daniel Skenandore, who has been missing for over 20 years, is an example of one such man.

He was last seen in Black River Falls, Wisconsin by friends who said Skenandore wanted to travel to Wyoming, according to a detective interviewed by local media.

However, he was never heard from after he called his girlfriend at 8 p.m. on Apr. 26, 1996 to tell her he would be working late.

There has been scant coverage by media in Green Bay; outside of Green Bay, there has been almost none.

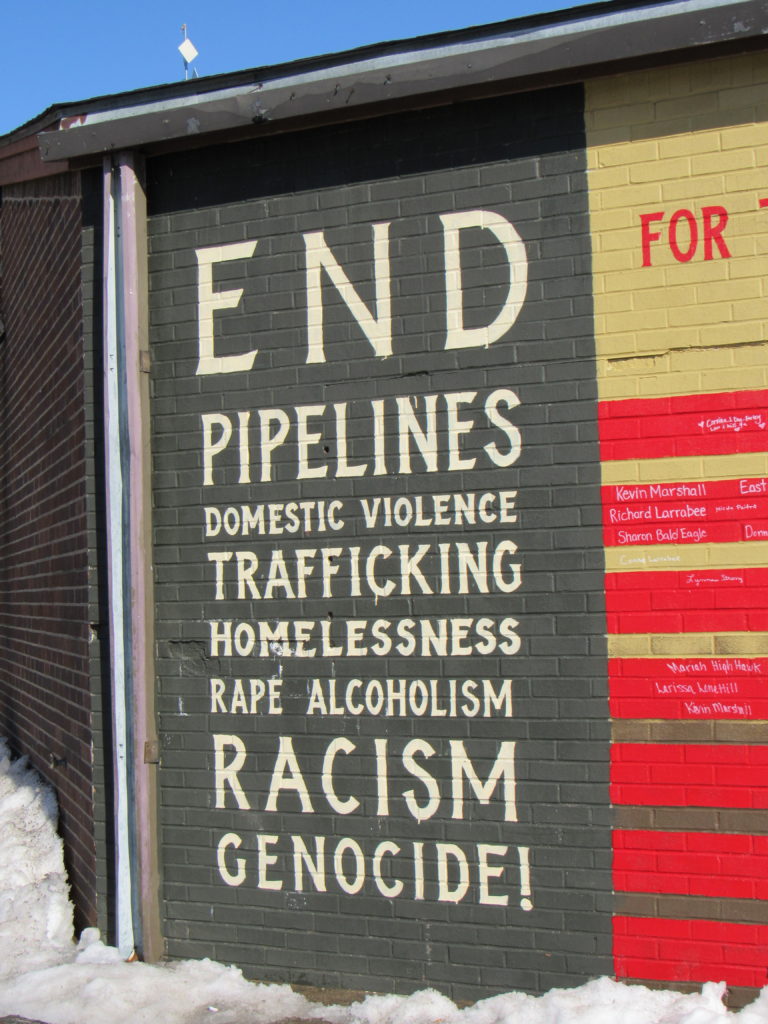

The intersectionality is clear, and for many Native people, so is the motivation.

“In general, women of color who go missing are not profiled in the media… [because] their cases are not important enough to warrant media coverage,” said Sarah Deer, a Native American lawyer, advocate and professor at the Mitchell Hamline School of Law.

And this isn’t a new phenomenon.

A 1992 study by Robert Entman found racial bias which consistently criminalized non-white groups, while Herbert J. Gans’ 1979 book “Deciding What’s News” explored how the news’ ethnocentric and middle-class skew makes stories about non-white, working-class and similar groups less important.

Deer said unequal coverage is not only unfair, but reduces the chances other missing people can be found:

“If the media is not covering it, then people won’t know to look for these women.”

So they don’t.

U.S. Rep. Ruth Buffalo, who represents the 27th District of North Dakota, said Native people still fight for recognition as humans, let alone victims worthy of news coverage.

“Many people believe there is still so much work to have indigenous people recognized as humans,” she said.

In fact, in 2007, the U.N. made a Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, which recognized, “… the urgent need to respect and promote the inherent rights of indigenous peoples.”

Buffalo, who was born in Mandaree, said Native people have struggled to gain respect since “first contact” — a euphemism for the colonists who came to claim their land.

And the media has become more of a problem than a solution.

“I think, in general, it’s an issue for indigenous people to have proper coverage in the media, accurate coverage,” she said. “There are a lot of stereotypes against Native Americans, like oh, they just take off.”

And sometimes they do; but not at a rate less than their white counterparts who are highlighted in the media.

Of the 612,846 missing person entries for 2018, over 90% (553,065) were cancelled, according to the FBI’s National Crime Information Center.

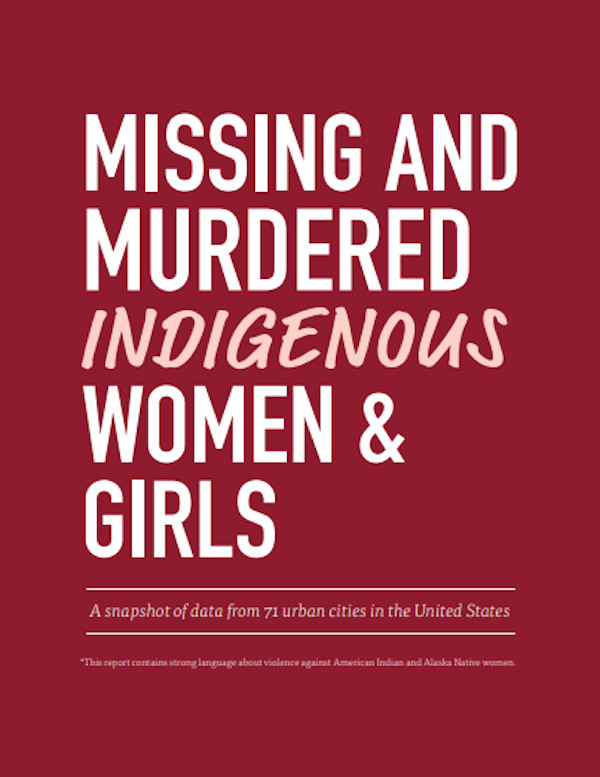

Doctoral candidate Annita Lucchesi and Urban Indian Health Institute Director Abigail Echo-Hawk, who identified 506 cases of missing and murdered native women after sending open records requests to 71 police departments, also identified several media shortcomings in their report.

They analyzed 934 articles on the cases they found and discovered that 95% of the 506 cases were not covered by national media at all, indicating that most coverage is localized.

Moreover, of the 934 articles they analyzed, violent, disparaging and/or dehumanizing language was used:

- Over one-third (38%) referenced drugs or alcohol

- One-third (33%) misgendered trans-women

- Nearly one-third (31%) referenced the victim’s criminal history

- One in ten (11%) referenced sex work

Buffalo said the media should focus on solutions instead of victim shaming, blaming or ignoring.

“We just have to look at what facts are present and the lack of media coverage or response does make one wonder … Does implicit bias play a role and how do we work towards addressing that ?” She asked.

Some of the journalists who covered the area, however, argue they are often hamstrung by an uncooperative tribal police force and suspicious Native American community.

Stu Merry, a reporter for the BHG news service, lives in Garrison, North Dakota, 20 miles from the Fort Berthold White Shield reservation line.

When he was a reporter, he said tribal police never shared information.

“Anything that happens out there, it goes into a black hole,” he said. “You will not get anything from tribal officials.”

“They’re very nice people out there, they’re just protective,” he added.

Jenny Michael, who worked at the Bismarck Tribune, said she doesn’t remember tribal police ever returning a phone call in eight years.

“Culturally, it’s just different,” she said. “They’re not super open to talking about a lot of this stuff. And I don’t know if that’s just cultural or just years of being beaten down by the poor system they have to deal with. “

But these jurisdictional quagmires don’t prevent broadcasters from putting up a missing indigenous person’s photo, describing the circumstances of their disappearance or publicizing a tip line every day someone is missing.

The difference, Deer said, is indifference.

“I don’t think (these cases) are straight forward, but I do think that what we have is official indifference in many cases,” she explained. “We’re not valued.”

“When Elizabeth Smart goes missing, everybody looks at her and she’s on CNN and, and you know, prime time news. But when a woman of color goes missing, especially a woman of color that might be a sex worker or might have an addiction problem or has been homeless … they don’t prioritize that disappearance.”

Robin Lynn Fox, a Native American mother from Fort Berthold went missing in 2014, yet was never searched for in Google. Searches for Jessica Heeringa, a white mother who disappeared from a gas station in 2013, reached peak popularity weeks after her disappearance and continued to to be searched for after.

Heeringa’s case appeared on Unsolved Mystery, an Investigation Discovery series called Disappeared, The Vanished podcast and Crime Watch Daily.

Fox’s case has yet to receive similar coverage on a television show.

Gene Cloud, a Native American man who went missing from Jackson, Wisconsin in 2012, also went missing with very little of the public consciousness being raised.

In fact, only five articles about his disappearance are available on the web.

In comparison, Gavin Smith, a 57-year-old white film executive who disappeared in California during the same year, reached peak popularity in Google searches during the month of his disappearance even in Wisconsin, where Gene Cloud was from.

Gavin’s body was found in 2014 and someone was been convicted of his murder in 2017.

Cloud has never been found.

Gene Jacob Cloud Jr., who went missing from Black River Falls, Wisconsin on January 25, 2012, would be 27 now.

He went missing on a stretch of Highway O, where a sheriff noticed his truck in a ditch, and says Cloud ran off into the woods before he could approach.

According to one of the five articles about his disappearance, he had recently started classes to earn his high school diploma and when he went missing, he left behind a pregnant girlfriend and a grieving mother.

Cloud, like other Native Americans who go missing, was valuable.

His family, like so many other Native American families, have missed him since he disappeared.

And for all intents and purposes, so has the media.