At night, Fort Berthold loses its stars.

Troika Yaskovic, an 18-year-old working at the Four Bears Casino gift shop, said, “You can’t see the sky because the smoke is so thick.”

So it’s only fitting that Annita Lucchesi, called “Evening Star Woman” (Hetoevėhotohke’e) in her language of Cheyenne, would come to shine a light on the abuses faced by her people.

Lucchesi became invested in researching violence because of her own experiences.

“I’m a survivor of sexual violence and human trafficking,” she said “It’s a violence that almost ended my life.”

So while studying for her master’s degree at Washington State University, she partnered with Abigail Echo-Hawk, director of the Urban Indian Health Institute, to send open record requests to 71 police departments across the nation.

From the responses, they compiled their 2018 report Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls.

The results were shocking:

- There were 5,712 cases of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls reported in 2016, but only 116 were logged into the DOJ database

- The majority of Native Americans (71%) live off the reservation

- They identified 506 cases of Native women and girls, which were likely undercounted due to their presence in an urban area. Of those, 128 were missing persons cases, 280 were murder cases and 98 were cases with an “unknown status”

- Half of the perpetrators identified were non-Native

- The Northern Plains, which included the states of Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska and Colorado, had the second-highest number of cases involving missing and murdered indigenous women and girls

- Only 40 agencies of the 71 asked provided data

- More than 95% of the cases in the study were not covered by national media

Unlike many of those cases, however, Lucchesi and Echo-Hawk’s work brought national attention to the issues with data collection and ripple effects those issues have had on police and media efficacy.

“It reached everywhere,” she said. “I knew the stories was powerful, and it’s been really encouraging about how it has sparked.”

After writing the report, Lucchesi began Sovereign Body Institute, a non-profit organization advocating for survivors of sexual violence.

It is, as she says, her life’s work.

And that work, Lucchesi said, has helped her, and the families of the victims, heal: “A database is a process of prayer,” she said. “I don’t add to the database every day. When someone goes through extreme trauma, those pieces of your spirit bend. The process of the database is a deep sense of urgency (to bring) all these spirits home.”

Raylene Wolf did that for one Wisconsin tribe.

Currently the administrative assistant for Wisconsin’s Great Lakes Intertribal Council’s Aging & Disability Program, Wolf once worked for the La Courte Oreilles police department, where she helped set up the tribal police department with NIBERS, the National Incident Based Reporting System.

Started in 1988, NIBERS began as an offshoot of the Uniform Crime Report (UCR) and was developed to collect national data more efficiently.

“I got us set up and I believe we were the third tribe in Wisconsin to start reporting,” she said.

Although it took six months of training and three months of supervision, Wolf was able to connect the tribal data from the police department to a larger network, helping better track crime trends and direct resources throughout the region.

For example, once they were set up with NIBERS, the department collaborated with Sawyer County.

The move was a milestone because even though some tribes report health and police data to the Department of Justice to apply for grants, Wolf said many tribes keep their information in-house and don’t share it with the public or other police departments.

“Tribes are a lot more private with their information,” she said. “I suppose it’s more of a sovereignty issue with the tribes that most don’t report the information.”

The Wisconsin DOJ UCR database contains tribal crime data we compiled from every tribe in Wisconsin.

Media Milwaukee journalists requested reservation crime data from every tribe from Wisconsin.

Some Wisconsin tribes with police departments, such as the Lac Du Flambeau, require permission from their tribal council before they can release such information.

Other tribes in Wisconsin, such as the Sokaogon Chippewa, Bad River and Red Cliff tribes told Media Milwaukee journalists that they do not collect such data.

Consequently, we examined crime in all of the counties which include reservation land:

But North Dakota’s “Crime Stats” database only included three homicides for all violent crime on tribal lands in 2017 and Fort Berthold MHA Nation representatives denied Media Milwaukee journalists access to their records.

Only crime data from North Dakotan counties with reservation lands were available.

Media Milwaukee reached out to former Fort Berthold Police Captain Grace Her Many Horses for an explanation, but despite several attempts, she did not return any of our calls.

North Segment Councilwoman Monica Mayer, who oversees New Town, North Dakota, said the lack of tribal and county data collection presents challenges for her as a policymaker because it’s difficult to create a solution for a problem you can’t see.

She also pointed out how collecting tribal data is just one of the concerns for the indigenous people of Fort Berthold, where the influx of drugs and alcohol from the oil boom have escalated rates of domestic violence, human trafficking and other violent crime.

Nationally, the trend toward higher death rates from drug and alcohol addiction, as well as homicide and suicide, is even clearer.

Tim Purdon was the United States Attorney for the District of North Dakota from 2010-2015.

During his work with tribal, county and federal law enforcement to increase public safety in Indian Country, Purdon said he saw first-hand how poverty contributes to addiction and violence.

“Reservations in my part of the world, the Great Plains, they suffer from tremendous challenges,” he said. “These are economically challenged areas … higher levels of addiction lead to higher levels of violence.”

Unemployment and poverty levels also lead to addiction and violence.

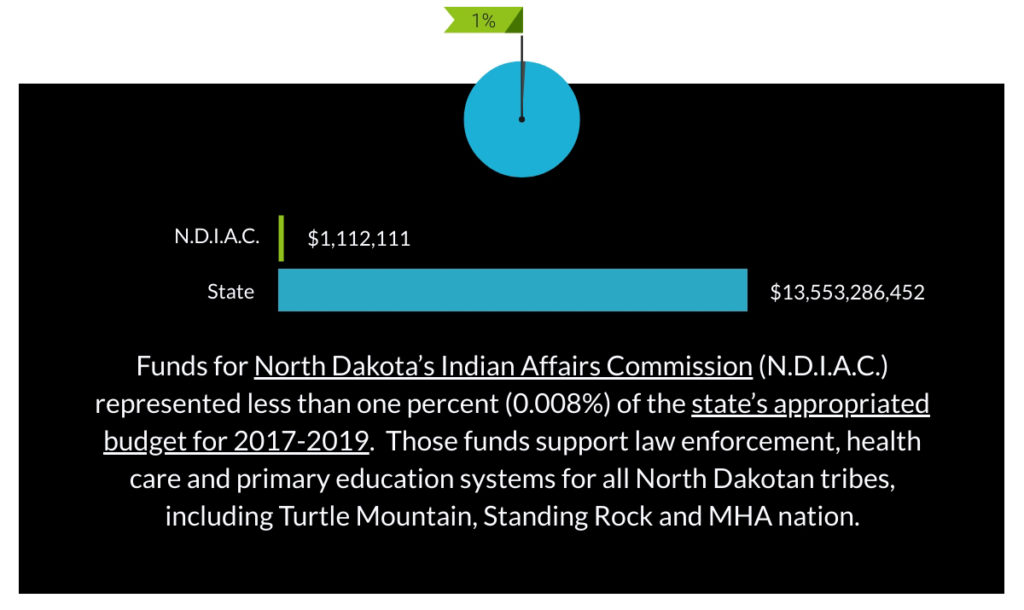

Purdon also said tight budgets make it incredibly difficult for North Dakota’s tribal police departments to collect tribal data.

“Tribal governments are not well-funded and the federal government has not lived up to its treaty obligations,” he explained.

As a result, he said, “data collection on reservations is not great.”

Janet Franson said the lack of accurate data collection by non-Native government agencies, such as state and local police departments, has a different cause: inefficacy.

“There are no numbers because nobody has given a damn enough until recently,” she said.

Franson, a retired former homicide detective, created Lost and Missing in Indian Country to track the number of missing Native women and girls, an uneasy feat given the fact that many are ruled accidents or suicides.

For example, Franson believes the death of three-year-old Keara Lee Coshow, who died in a fire that was ruled accidental, was actually due to child abuse.

According to the girl’s sister, Coshow had been shaken into unconsciousness before the fire occurred and months earlier, was blinded after Drano cleaner from a childproof canister made its way into her eyes.

However, no one has ever been charged in connection with the Lac Courte Oreilles girl’s death.

Franson described this carelessness as a reflection of how often Native people are ignored by non-Natives.

Her website, along with Justice for Native Women, the Native Alliance Against Violence and countless Facebook pages, is dedicated to Native people believed to be missing, murdered or gone.

It’s one way individuals are attempting to make those cases more visible and solvable. And although the sites are not perfect, government data entries are not either.

For example, law enforcement voluntarily adds missing people from their jurisdiction to NamUS, resulting in gaps and the DOJ-run Wisconsin Clearinghouse is missing Timothy Thompson.

But even without all the numbers, existing data from NCIC illustrates a more disturbing picture:

The chart above divided the U.S. Census Bureau population for particular races in specific years and dividing that figure by the number of missing people for particular races reported by the FBI’s NCIC for the corresponding year. The result of that calculation was then multiplied by 100,000, producing the rates of missing persons per 100,000 people in that racial category.

American Indians and Alaska Natives, represented by the purple line on the chart, have consistently illustrated the second-highest rate of missing people in the country, according to FBI statistics.

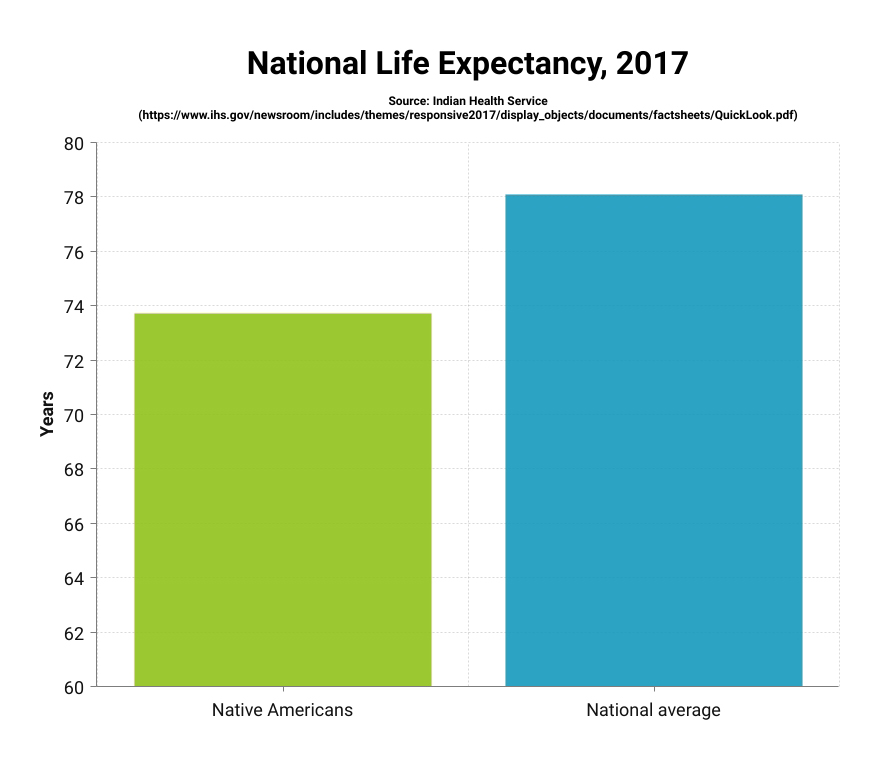

Moreover, predators, poverty, addiction and a lack of resources mean American Indian/Alaska Natives do not live as long as average Americans.

But for many Native Americans, numbers only show half the picture.

The other half can be heard in the dead of night, from the voices of Native Americans singing prayers to their ancestors.

It smells like burnt sage offered as thanks and goodwill to the spirits; tastes like the Three Sisters of corn, beans and squash Bernadine Young Bird keeps alive in the Hidatsa tradition of gardening; and is envisioned in the traditional garments of men like Eric Bears Paw, who adorn their carefully sewn and beaded ensembles with otter pelts.

And on the other half of each number is a loss that can be felt — a life, a voice, a face gone.